Oceana’s Statement on President Marcos Jr.’s announcement on the Construction of Fish ports and cold storage facilities to address the Post-Harvest Losses in Coastal Provinces in the Philippines

Oceana lauds the announcement of the President to prioritize the construction of fish ports in 11 coastal provinces and the rehabilitation of 20 identified municipal fish ports, aimed at decreasing post-harvest losses through the construction of cold storage facilities in fish posts nationwide1. This is welcome news for our artisanal or municipal fisherfolk, especially in coastal areas that could not scale up their post-harvest and cooperative opportunities due to the absence of facilities.

It is worth noting that these initiatives are aligned with the policy objectives that have been in place since the 1998 Fisheries Code. As stated in Section 2(e) in Republic Act 8550, as amended by Republic Act 10654, the State must provide, first and foremost to the municipal fisherfolk, any appropriate technology, research, financial, and marketing assistance support, including the construction of post-harvest facilities. But these policy objectives hardly reflect the realities on the ground. In fact, because of the lack of post-harvest services in their areas, artisanal fisherfolks have learned how to fend for themselves, such as the women fisherfolk in Victoria in Northern Samar and Ragay in Camarines Sur by organizing themselves to reduce post-harvest losses.

The facts are clear. According to the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources, the country’s current fish spoilage is between 25 to 40 percent due to a lack of post-harvest equipment2. This converts to major losses in income for the fisheries sector. But more than the band-aid solutions that are provided in the government’s plans to address this recurring problem, we need to enable a better fisheries governance system that ensures inclusive, transparent, participatory, and accountable mechanisms are followed. Otherwise, we will end up with facilities that will be left un-used, under-utilized, improperly managed, and worse, become “white elephants”.

While the government seeks to reduce spoilage to 10-15%, it must first recognize the fact that solving this problem is not as simple as providing ice machines or freezers. These are good steps; however, these are only a small part of the entire value chain that starts with the fishers and ends with the consumers.

As long as municipal fish catches remain to be many units of small volumes, the reduction of spoilage will always be elusive. Structural and/or organizational reforms of small fishers and fishing communities must be done in terms of landing their catches, making locally available seafood, and/or transporting them to urban centers within and outside of municipalities. This can help reduce the prices of fish in the markets. At the same time, the processing of fish and aquatic products must also be based locally so that more money is retained locally, and local economies will grow.

Likewise, it is important to conduct a thorough assessment of the government’s past programs relating to post-harvest activities and apply lessons from these in designing, planning, and implementing new programs. Otherwise, we will be repeating past mistakes and simply wasting limited government resources on initiatives that are doomed to fail in the guise of making us look and sound good.

An ecosystem-based approach to fisheries management is well-entrenched in our fisheries laws and regulations. This underpins the management of natural fishery management areas that are supported by research, technical services, andguidance by the State (Section 3f, RA 10654). Simply put, we cannot manage our fisheries ecosystems without the requisite technical support and services from the national government. However, the downward trajectory of fish stocks is a symptom of the fact that we are not effectively managing our fisheries.

One of the finest examples of this is the sardine fisheries. We cannot overemphasize the importance of sardines as the most accessible protein source for Filipinos. It makes up around 15% of the total fish catch. But despite its approval as a national management plan for 2020-2025 for sardines3, the plan tragically remains on paper. The Department of Agriculture through the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources has not released the implementing guidelines for the plan. As a result, news about sardine spoilage continues to be reported in several areas of the country. We have to translate the plans into action and implement our National Sardines Management Plan immediately. The plan can contribute to the Marcos administration’s target to reduce spoilage to about 8-10% as it has been long the objective under the said plan to reduce post- harvest losses by 10% as early as 2022. There are no moral or legal reasons to delay the immediate implementation of the national plan to manage sardines.

Seafood is central to Filipino cuisine. This was confirmed in the State of Fish in Nutrition Systems in the Philippines report of the Department of Science and Technology – Food and Nutrition Research Institute and MRAG Asia Pacific4. The study shows that the highest consumption rates are in the Zamboanga Peninsula (Region IX), the Western Visayas, and Caraga regions5. Likewise, despite the availability of locally caught fish, food security and fish consumption is decreasing over time, particularly in low-income and rural households, because of the increasing price of food, a growing population, unsustainable development, and impacts from natural disasters (climate change), and lingering effects of the pandemic. Hence, it strongly recommends to prioritize the sustainable management of our fisheries and the wellbeing of artisanal fisherfolks for food and nutritional security and livelihoods to reduce hunger and poverty incidence in the Philippines6. As emphasized time and again, municipal, or artisanal fishers cannot remain the “poorest of the poor,” they produce nutritious food, yet they suffer from malnourishment7.

On a final note, food security for all Filipinos is the country’s ultimate challenge. But there is no doubt that we can achieve this lofty goal if we protect our food resources, especially those that come from our oceans. Thus, let us take immediate steps towards a more responsive, sustainable, pro-people, and science-based management of our fisheries, alongside complementary measures, such as improving post-harvest activities.

References and Facts:

- BFAR assures enough fish supply as Holy Week nears | Philippine News Agency (pna.gov.ph). Retrieved 20 March

- National Sardines Management Plan 2020 – 2025. https://www.bfar.da.gov.ph/wp- content/uploads/2022/07/National- Sardines-Management-Plan-with-ISBN.pdf. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- The State of Fish in Nutrition Systems in the Philippines A report prepared for Oceana MRAG-AP_State-of-FINS-PH.pdf (dost.gov.ph). June 2022.

- Muallil et, 2014

- Manila Bulletin: Marcos wants cold storage facilities at ports to counter fish spoilage

- Manila Bulletin: Build 11 fish ports in coastal provinces — PBBM

- Marcos wants cold storage facilities at ports to counter fish spoilage (mb.com.ph)

- Sardine Beaching in Masbate

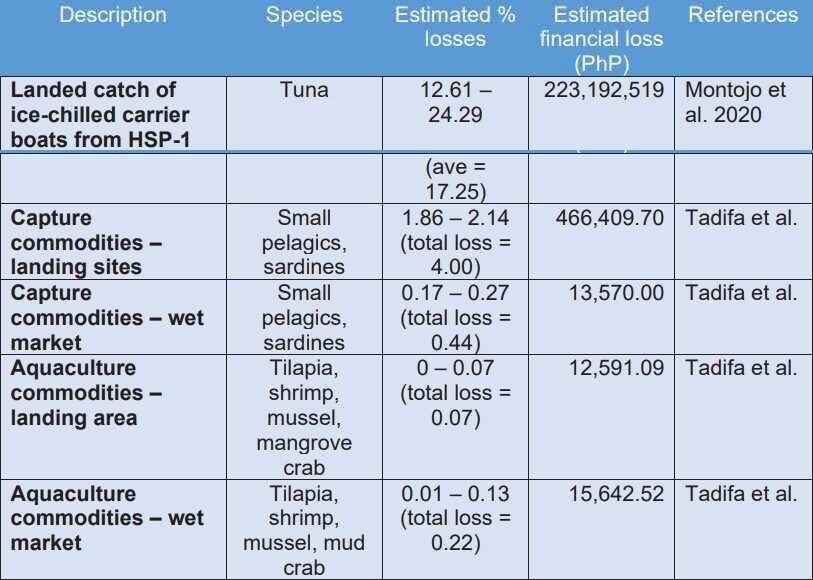

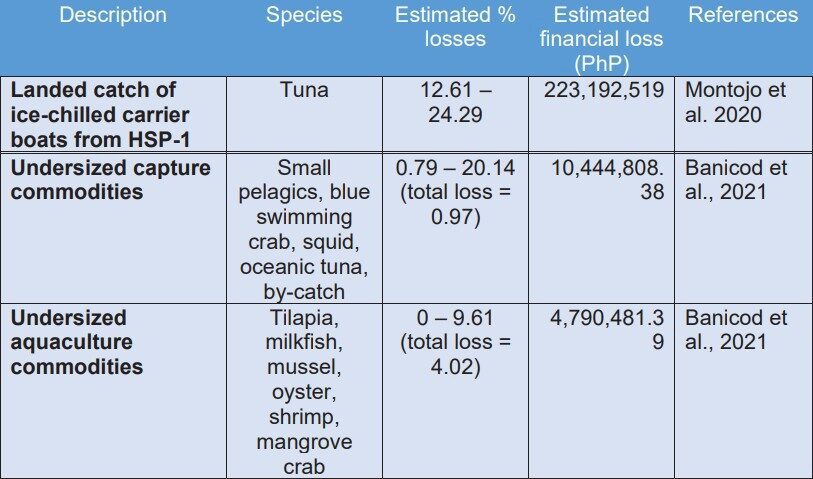

Post Harvest Data: There is not much granular information marine capture fisheries postharvest losses but some studies on selected sites8.

- Market force loss (MFL) – caused by unexpected market supply and demand

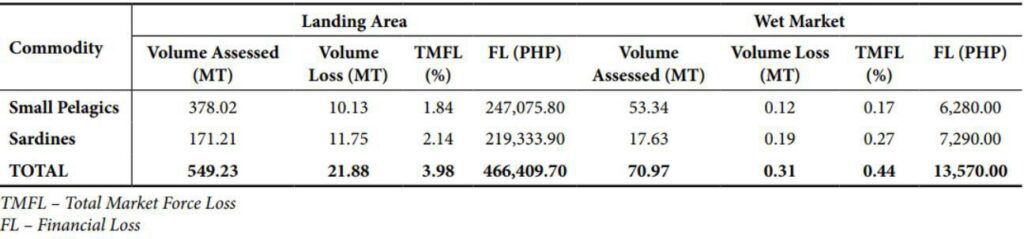

- Highest loss in landing sites was recorded in sardines at 14%, documented loss for mixed pelagic species was estimated at 1.84%. Small pelagic such as anchovies, scads, neritic tunas, mackerels, fusiliers, and sardines are susceptible to MFL due to their seasonality.

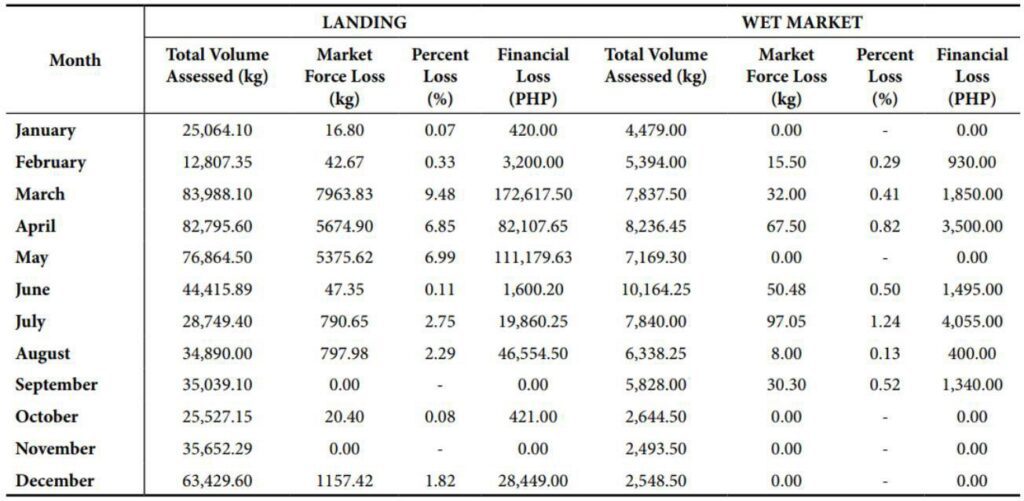

Monthly loss in landing sites ranged from 0% to 9.48%, with a higher percentage of losses recorded from March to May that correspond to peak fishing season

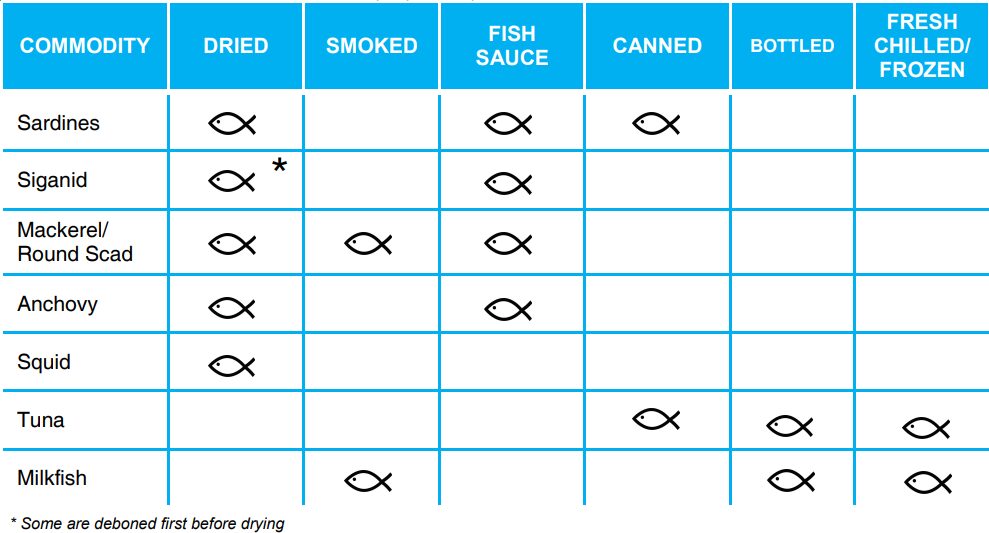

NFRDI conducted several fisheries post-harvest losses studies in 2018 as shown in the table below9

- About 20-40 percent of total fish caught and farmed is lost annually, with additional loss of quality and nutritional value, due to poor post-harvest practices often associated with inadequate infrastructure for ice supply, safe handling and cold storage and transport of seafood10

- To reduce spoilage, maintain quality, and produce safe and competitive fish and fishery products, several fish processing methods are used in the Philippines. Such preservation and processing techniques involve any of the following: (1) temperature control, either low temperature (i.e. chilling at 0-4 degree Celsius or freezing at 18 degree Celsius) or high temperature (i.e. thermal processing, boiling and smoking); (2) moisture reduction(i.e. salting, drying, smoking and fermentation); (3) other processing methods (i.e. mincing, surimi processing, seaweedprocessing, marinating/pickling, ); and, (4) combination of several techniques to produce high value products11

- Fish species thatare caught in large quantities during their peak seasons such as sardines (tamban), siganid (danggit), mackerel/round scad, anchovies and squids are usually the ones that are being traditionally processed

The PFDA eight (8) regional fish ports are all operational but the facilities need to be improved/ rehabilitated to conform with HACCP and GMP standards/SSOP.

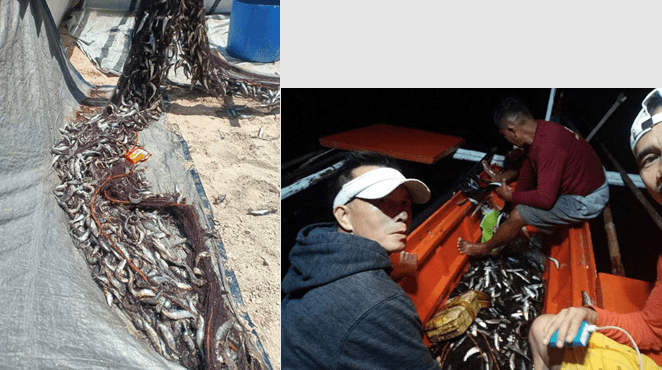

Artisanal Fisherfolk Post Harvest Efforts/Initiatives:

Bottling of sardines in northern amar

Fish Drying in Ragay, Camarines Sur

Issues on Sardine Spoilage (Medellin, Cebu) – Photos from Ven Carbon:

Sardine Beaching in Masbate 12

1 Marcos wants cold storage facilities at ports to counter fish spoilage (mb.com.ph). Retrieved 20 March 2023.

2 BFAR assures enough fish supply as Holy Week nears | Philippine News Agency (pna.gov.ph). Retrieved 20 March 2023.

3 National Sardines Management Plan 2020 – 2025. https://www.bfar.da.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/National-Sardines-

Management-Plan-with-ISBN.pdf. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

4 The State of Fish in Nutrition Systems in the Philippines A report prepared for Oceana MRAG-AP_State-of-FINS-PH.pdf (dost.gov.ph). June 2022.

5 Muallil et al., 2014

6 The State of Fish in Nutrition Systems in the Philippines A report prepared for Oceana MRAG-AP_State-of-FINS-PH.pdf(dost.gov.ph). June 2022.

7 The State of Fish in Nutrition Systems in the Philippines A report prepared for Oceana MRAG-AP_State-of-FINS-PH.pdf(dost.gov.ph). June 2022.

8 Tadifa et.al. 2022. A study on postharvest losses in fisheries owing to changes in marker supply and demand in the Philippines. The Philippine Journal of Fisheries. 29 (1). https://www.nfrdi.da.gov.ph/tpjf/etc/A%20Study%20on%20Postharvest%20Losses%20in%20Fisheries%20Owing%20to%20Cha nges%20in%20Market%20Supply%20and%20Demand%20in%20the%20Philippines.pdf

9 https://www.bfar.da.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Comprehensive-National-Fisheries-Industry-Development-Plan- CNFIDP-2021-2025.pdf

11 https://www.bfar.da.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/CPHMAIP20182022.pdf

12 https://www.facebook.com/sunstarcebu/posts/pfbid0yWPk3NVVfXSLctZ75RDnyBsSaVbatdZmQTNWtEhcrfes7y14htG7uRQnZ vhdk7EHl https://www.facebook.com/bfarbikol/posts/pfbid02cUrKZJv8tVfmX3bPTGSiM1nEK6M4VXmWxFMh3NZiwLWZXfVdx4n43 xo4 zv8nmbRl